1.14. Part4. A Cup of Tea meets Heart Sutra

The tea nudged me gently, as if awakening something long forgotten. Without thinking, my lips began to move, softly reciting the first line of the Heart Sutra:

19. Taste of Chinese Green Tea

Memories are engraved along with the five senses. I've already forgotten the Chinese monk's name, but I remembered a sip of green tea he made for me. It was a novel way of pouring tea leaves directly into a thick, worn glass and drinking the tea after the leaves had sunk. Surprise and excitement had wrapped around me. While waiting for the tea leaves to sink to the bottom, he showed me his kung fu. It was my first time to be treated like a princess, so I raised my glass as if I were an ancient Chinese princess and looked at him through the pale green of the jade. He looked like a jade crane dancing in a tea forest.

I closed my eyes and gently untangled the forgotten memory.

The first sip was soft and smooth,

cradling the tongue with subtle sweetness,

like a quiet stream winding through mossy stones.

Hints of grass and floral whispers lingered gracefully,

with a calm, lingering finish that evoked serenity and tradition.

Under the summer sun,

each note unfolded gently, like a soothing rain.

The taste surprised me—so different from the Japanese green tea I had always been familiar with.

Japanese tea strikes the senses with vivid liveliness—

a breath of fresh spring air, infused with vibrant umami.

It is sharper, more direct, with a clean, vegetal punch,

like biting into a tender leaf.

My palate awakens, light and brisk, filled with a sense of clarity.

The flavour carries hints of seaweed, grassy meadows, and a touch of sweetness.

It leaves a crisp, invigorating aftertaste—

as if nature itself had been distilled into a single sip.

I thought: "Ah… It’s just like the sound of languages."

Chinese green tea is multifaceted, layered, and expressive, while Japanese green tea is natural, honest, and clear.

The question lingered in my mind for days, weeks, even years. Why was the taste so different? Why did they both soothe, yet in such distinct ways?

It wasn’t until two years later, in Hong Kong, that I began working as a tea buyer, and then I finally asked the question out loud.

The one that had brewed quietly within me since that first surprising sip.

She was the one who answered, a graceful Chinese tea master with porcelain-like skin and eyes that seemed to read my thoughts. In one of her lessons on tea, she poured tea with the elegance of a poem, and said gently,

“It’s in the way we stop time.”

I look up into her eyes. This was my turn to read her thoughts. She explained,

“In Japan, they steam the leaves to preserve their green vitality—bright, grassy, and direct. In China, we pan-fire them gently in a hot wok—bringing warmth, depth, and roasted sweetness.”

Then she smiled and said, “But both carry the same spirit. They calm the body, awaken the mind, and dissolve the weight we carry—because in every leaf, there is something ancient that remembers how to heal.”

She poured tea in silence—no performance, no showmanship—only presence. The steam curled upward like a spirit rising. Her hands moved with intention, neither rushed nor hesitant. When she looked at me, it felt as though she was seeing "through" me, not past me.

“It’s in the way we stop time,” she said.

And as she explained the difference—steam and fire, vitality and warmth—I felt something loosen inside me.

Not just an answer to a question, but a shift in the way I perceived the world. I wasn’t only drinking tea. I was tasting "heritage", "geography", and "philosophy"—the soul of mountains, rain, and human hands transformed into liquid clarity.

I stared at the pale green in my cup, and it stared back at me, holding a silence that stretched across cultures and years. A silence that invited me inward.

She said nothing more. She didn’t need to.

The tea had already spoken.

As I walked out of her shop into the Hong Kong light, something within me stirred. Now, two decades later, that something stirred within me again. I recognised it was the voice of the tea.

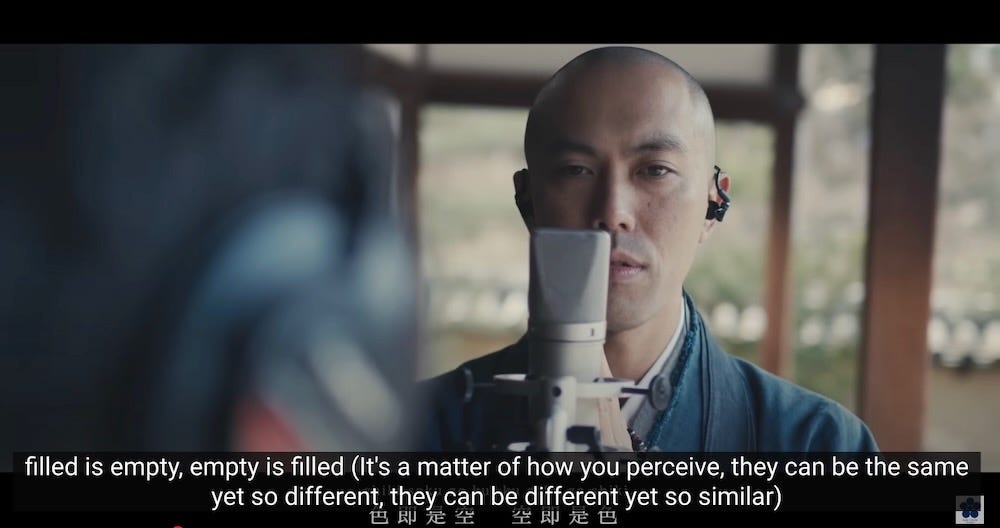

The tea nudged me gently, as if awakening something long forgotten. Without thinking, my lips began to move, softly reciting the first line of the Heart Sutra:

“観自在菩薩(Kan Ji Zai Bosatsu): The Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (a compassionate, enlightened being)

行深般若波羅蜜多時(Gyo Jin Han Nya Ha Ra Mi Ta Ji): While practicing deeply the perfection of wisdom

As the words left me, I felt my breath deepen. The sutra’s rhythm carried me inward.

20. Who is The Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara?

The Heart Sutra appears to be a story of the Bodhisattva, a significant and widely revered figure in Buddhism, particularly in the Mahayana tradition. Avalokiteshvara, as a Bodhisattva, has vowed not to attain complete enlightenment until all beings are enlightened. Because of this strong vow, Avalokiteshvara embodies boundless compassion.

In East Asia, for example, the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara is often depicted as a gentle figure and is sometimes known as Guanyin (in Chinese) and Kannon (in Japanese). Many people turn to this figure for comfort and aid in moments of trouble.

I recited the following lines.

照見五蘊皆空(Sho Ken Go Un Kai Kū): The Bodhisattva sees when the five aggregates are all empty,

度一切苦厄(Do Issai Ku Yaku): The bodhisattva frees all beings from suffering and difficulties.”

I had heard the word “Go Un” many times and remembered it, because it sounds like “Five clouds” in Japanese. As I looked at the clouds in the sky, with the memory of the lingering sweetness of tea on my tongue and the Chinese tea master still fresh in my heart, I felt, imagined, moved and recognised “Go Un”.

The Buddha once taught that what we perceive as "I or Self" is not a fixed being, but a shifting constellation of the "body" and the "mind," and that the mind is further divided into four parts. The function of one body plus four minds is “Go Un,” the five aggregates.

21. What are the functions of the Five Aggregates?

“Form” is the body, the tangible world shaped by the four elements—earth, water, fire, and wind. These are what the sutra calls “色 (shiki)”— ”colour”. Not just visual colour, but all things with form and weight: the body, the sky and the cup of tea. Everything we can touch or name.

“Feeling” is the first function of the mind. It arises when form meets the senses. This is what the sutra calls “受 (ju)” — “receiver”. A taste, a breeze, the warmth of the sun—these are the sensations that ripple through us, the way the mind receives the world.

Then comes “perception”, the second function of the mind—the mind’s act of labelling what it senses. This is what the sutra calls “想(sou)— “thought”. The face of a stranger, the scent of plum blossoms, the shape of a memory. These are not the things themselves, but our minds’ reflections.

“Mental formations” follow, the third function of the mind—habits, emotions, intentions. This is what the sutra calls “行(gyo)”— “action or reaction”. These are the invisible winds that move us, rooted in past actions and feelings, shaping our thoughts and reactions.

And beneath them all flows “consciousness”—the awareness that knows the sensations, the thoughts, the breath. This is what the sutra calls “識(shiki)”— “recognition”. We recognise something as an object, experience it, or turn it into knowledge. However, like a current, it flows, but never holds still.

I looked up into the sky as I came to a deep understanding: “Who I am is how I seem to be, moment to moment.”

The sky was pale blue, with hints of grey and violet near the edges. My brain whispered, “Colour, that is the sky, the sky, that is colour.” Due to destiny, I was born in Japan and spent time with a Chinese monk in a Zen temple in China. It tickled something in me and persuaded me to observe the sky from that perspective. However, that memory, too, was a form—empty, and yet, somehow, deeply real.

Air itself, I reminded myself, is generally colourless and transparent. The blue colour of the sky isn't due to any inherent hue in the atmosphere, but instead results from how molecules and particles in the air scatter sunlight. The visibility of blue graduations in the sky stems from light scattering; specifically, shorter blue wavelengths are scattered more effectively than other colours, creating the sky's blue appearance in our eyes. So, the atmosphere isn't inherently colored; our perception, shaped by physical processes, gives the sky its blue hue. What we see as form is created by something empty; what is empty gives rise to form.

“Shiki soku ze kū, kū soku ze shiki.” "Form is emptiness, emptiness is form."I chanted again.

Just as the tea’s flavour was both subtle and vivid, just as the self is both here and not here, the sky was a reminder:

We live within illusions shaped by truth, and truths that dissolve into illusion.

To taste tea deeply is to taste impermanence.

To observe the sky is to glimpse the Heart Sutra itself.

And I was ready now to listen, to look, to understand. Let me delve into the Heart Sutra.

22. What is the Heart Sutra?

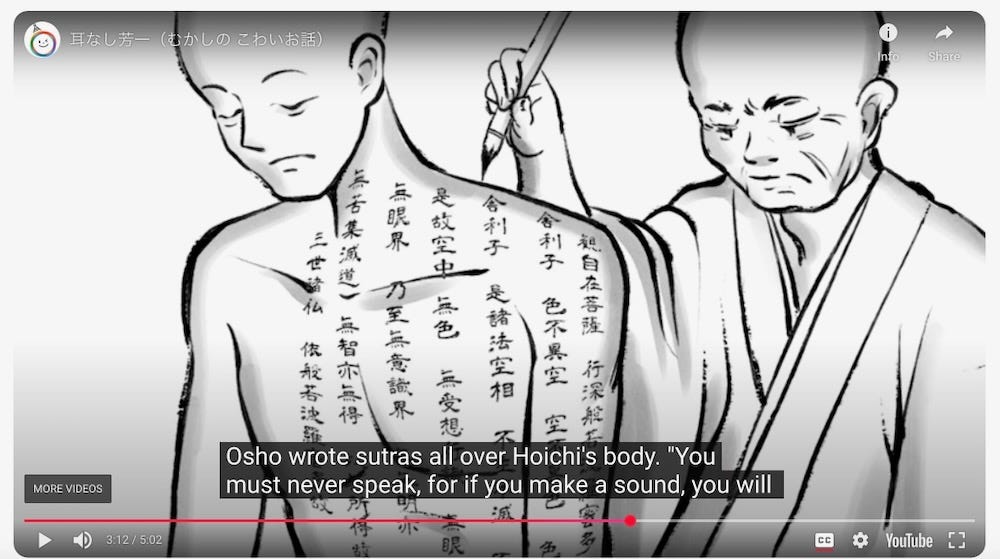

In Japan, the Heart Sutra is known as “Hannya Shingyo” and is believed to possess the power to ward off evil spirits and curses. I first became aware of it during primary school when I read the ancient tale "Hoichi the Earless." The story is so frightening that every Japanese child grows up believing in the clandestine power of the Heart Sutra. At least, I do.

The tale of "Hoichi the Earless" is a classic Japanese ghost story from Lafcadio Hearn's collection, "Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things." Kaidan: 怪談 means ghost stories in Japanese.

The story centres around Hoichi, a talented but blind monk famed for his masterful biwa (a traditional Japanese lute) playing, known as a “Biwa hōshi.” One night, the spirit of a Heike clan samurai—a warrior who perished during the Genpei War (June 1180–April 1185)—visits him, requesting that Hoichi perform for the spirits of fallen warriors. Unaware of his ghostly audience due to his blindness, Hoichi is taken to a haunted graveyard, where he performs for spectral spectators. Impressed, the samurai spirit invites Hoichi to continue entertaining their clan.

However, as Hoichi becomes increasingly immersed in the supernatural realm, he becomes vulnerable. To avert spirits from becoming overly attached, a protective monk at his temple inscribes the Heart Sutra on Hoichi’s body, but neglects to cover his ears. When the spirits return, they notice that only his ears are exposed. Enraged, they sever his ears as a warning, leaving Hoichi permanently deaf in that regard.

The story ends with Hoichi gaining fame despite his loss. Still, he is haunted by the memory of that night, illustrating themes of vulnerability, the supernatural, and the cost of artistic talent.

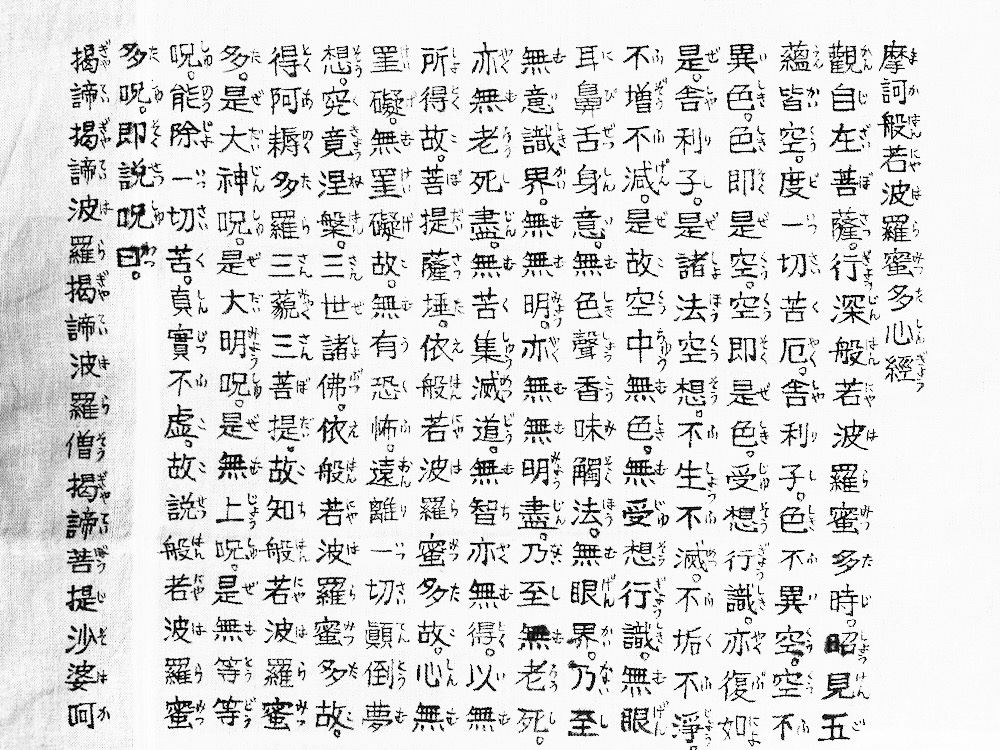

The second time I encountered the Heart Sutra was when I left Japan. My mother wrote the 262 words with ink on pure cotton fabric. I visionarily saw it, but I didn’t understand Chinese at that time.

Shortly after Buddhism was introduced to Japan, copying sutras, known as "Shakyo," became an essential method of absorbing teachings from abroad. Monks practised this as a form of self-awareness and training, based on the belief that Buddha resides within each character. Exceptionally, beautifully written sutras in a powerful style served as models for subsequent copyists. Even today, the profound and mysterious power of copying Buddha's words continues to captivate people.

The third time I met the Heart Sutra in my life was in L'ESCALA, Spain. Before meditation, we recited it aloud with my meditation teacher, Satchidanand, and his partner, Devi. I directly experienced the power of this sutra, which I had believed in since I was a child, through “Hoichi the Earless”; my mother had copied it for me as a form of protection. More than the sense of security that I was protected from evil spirits, I felt a refreshing exhilaration, which opened up a new vista into the secret of the universe and energised me to seek this hidden knowledge.

I noticed that we recited it in Japanese on-reading, not Chinese reading.

I've experienced a bizarre feeling in my brain. My brain recognises these as Japanese, but my thoughts don’t understand them through my ears, but they do from the visual memory of my mother’s copy.

Moreover, in the last part, “GYA TEI GYA TEI HA RA GYA TEI HARASO GYA TEI BO JI SOWA KA”, the more I chanted, the more I felt like this mystery was engraved in my mind; I received an effect just from the sound.

The Heart Sutra's real name is “Ma Ka Han Nya Ha Ra Mi Ta Shin Gyo.” The original was written in Sanskrit as "Mahā Prajñā Hārī Mṛta Śūnyatā."

Mahā (महा) meaning "great" or "big"— “Ma Ka” stays the same as the Sanskrit sound.

Prajñā (प्रज्ञा) meaning "wisdom"— "Hannya", wisdom

Hārī (हरी) meaning "to take away" or "to remove" — “Hara”, eliminating suffering or delusion

Mṛta (मृत) meaning "dead" — relates to“Mita”, which means to reach the state of enlightenment, associated with Nirvana (complete liberation )

Śūnyatā (शून्यता) meaning "emptiness" or "void" — relates to "Shingyo" (Heart Sutra), teachings of the same mind as Buddhathe, which is a core Buddhist text discussing emptiness.

I slowly put all the elements which I discovered together.

The "Mahā Prajñā Hārī Mṛta Śūnyatā" was born in ancient India, composed in Sanskrit as a distillation of the Buddha’s insight into the nature of emptiness. As the teachings travelled across mountains and rivers into China, devoted monks translated their profound wisdom into their own language. Over time, at least seven Chinese translations emerged, each one carrying subtle differences, like different shades of the same light.

Yet not everything was translated. Certain sections—the mantras—remained in their original Sanskrit. These were not ordinary words. They were considered sacred sounds, powerful in their own right. To translate them might dilute their essence, their vibration. Therefore, the Chinese preserved them intact, transcribing their sounds using Chinese characters that mimicked the original syllables.

Eventually, the *Heart Sutra* reached Japan. There, the Chinese characters were imbued with “On-yomi”, the sound-based reading rooted in the original Chinese pronunciation. But more than that, the chanting began to take on the unique rhythm of the Japanese soul—a resonance shaped by the ancient relationship with nature that stretched back to the Jomon period.

The sutra evolved not just in form, but in spirit. It absorbed the prayers, voices, and devotions of countless practitioners across centuries and borders. What I recite now, flowing effortlessly from memory, is not just a text. It is a crystallisation of countless acts of reverence—a sacred transmission refined like tea, leaf by leaf, across generations.

And when I consider this—how many hearts, hands, and breaths have shaped the sutra that now lives in mine—I feel a quiet awe rising within me. It is more than scripture. It is the breath of ancient prayer. The echo of wisdom. A secret path toward nirvana, hidden in plain sound. It was brought from India to China. Many monks translated it into Chinese. There are seven versions of translation. Then, in Japan, the on-reading was added. There are sections called mantras, which are Sanskrit words kept in their original form. These mantras are considered powerful spells that possess spiritual potency. Because of this, they are often not translated into Chinese or other languages, as doing so could diminish their intrinsic spiritual power.

I looked up at the sky.

The vastness above mirrored the stillness within me, limitless, wordless, eternal. And then, like lightning through clear water, it struck me:

Everything I see—this life, this world, every face and echo-is arising from within me. My thoughts, my emotions, even the people I meet. They’re not random. They are the unfolding petals of a single inner process: a continuous self-renewal, life blooming out of mind.

And the moment I truly saw this, a quiet tremor passed through my body—a chill.

Then—perfectly timed, as if the world itself had been listening— a voice called out, clear and unexpected:

“Dobrý den! (Hello!)”

To be continued to 1.15. Depression

Dear Subscriber and Reader,

Thank you for sharing this quiet moment with me.

This chapter was born from a single, humble act: drinking tea. Yet within that stillness, the ancient wisdom of the Heart Sutra began to unfold—not as distant philosophy, but as living truth.

The tea became a mirror. The chant, a doorway. And in the silence between sips, the boundary between self and sky began to dissolve.

If even a fragment of that emptiness touched you—if the words stirred something quiet and luminous within—then the tea has done its work.

Let us walk gently into the next moment.

With gratitude,

Yuko

Beautiful and enlightening as usual. My beautiful & amazing soul sister. You put so much energy into me and lift me up. Thank you. ❤️